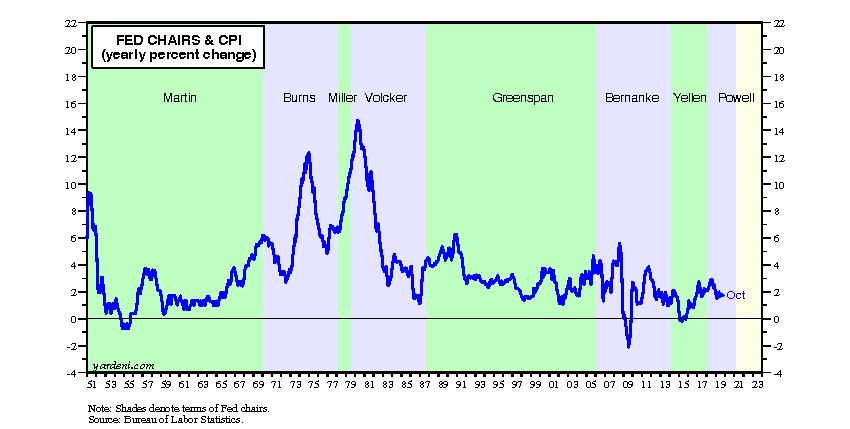

Former Fed Chair Paul Volcker passed away on 12/8. He broke the back of inflation. Unfortunately, he had to cause a recession to do so, which broke the backs of lots of good hard-working people. He was widely viewed by them as the Grinch Who Stole Christmas. All of the Fed chairs who came after have preferred playing the role of Santa Claus, showering us all with lots of easy money. They were able to do so mostly because inflation has remained subdued ever since Volcker subdued it.

Actually, at the end of last year, Fed Chair Jerome Powell seemed more like a Grinch than a Santa. He roiled the financial markets by suggesting that the Fed would continue to raise the federal funds rate three or four times during 2019. He started to change his mind just around Christmas of last year and signaled that the Fed would halt rate hikes for a while. He completed his pivot by lowering the federal funds rate three times this year, on 7/31, 9/18, and 10/30 (Fig. 1).

As a result, the S&P 500 stock price index bottomed on Christmas Eve last year at 2351.10 (Fig. 2). It was up 37.8% to 3240.02 on Friday, 12/27 (Fig. 3). That’s a very long Santa Claus rally.

At the 7/31 meeting of the FOMC, the committee decided not only to lower the federal funds rate, for the first rate cut since 2008, but also to terminate quantitative tightening (QT) ahead of schedule: “The Committee will conclude the reduction of its aggregate securities holdings in the System Open Market Account in August, two months earlier than previously indicated.” From 10/1/17 through 7/31/19, the Fed’s balance sheet was pared from $4.4 trillion to $3.7 trillion (Fig. 4).

The Fed and the other major central banks are all playing Santa during this holiday season and are on track to continue doing so in the new year:

(1) Fed. In a 10/11 press release, the Fed announced that beginning on 10/15 it “will purchase Treasury bills at least into the second quarter of next year in order to maintain over time ample reserve balances at or above the level that prevailed in early September 2019.” More details were released in a separate New York Fed statement (and accompanying FAQs).

The initial pace of these “reserve management” (RM) purchases will be approximately $60 billion per month and will be in addition to ongoing purchases of Treasuries related to the reinvestment of principal payments from the Fed’s maturing holdings of agency debt and agency mortgage-backed securities. As the new holdings mature, the principal payments will be reinvested again into T-bills.

Many have commented that these actions look a lot like quantitative easing (QE). After all, the Fed is expanding its balance sheet sizably, possibly by up to $300 billion or more assuming $60 billion a month through March as a ballpark figure. The Fed’s balance sheet totaled $4.0 trillion during the 12/4 week, including $2.3 trillion in US Treasury securities, of which $420 billion are Treasuries maturing in one year or less (Fig. 5). This portfolio of Treasuries maturing in under a year is up $71 billion since the end of September.

(2) ECB. Mario Draghi’s term as president of the European Central Bank (ECB) ended on 10/31. Before leaving, Draghi put together a monetary stimulus package. It is designed to induce Eurozone governments to borrow at zero or negative interest rates to spend on stimulating their economies.

The package includes an open-ended commitment to buy as much as €240 billion per year of bonds issued by Eurozone governments. In other words, Draghi set the stage for the implementation of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) in the Eurozone. According to MMT, governments should borrow as much as possible as long as inflation doesn’t heat up. All the better if the central bank enables such borrowing by lowering interest rates and purchasing government bonds—again, as long as inflation doesn’t heat up. Now it is up to the various Eurozone governments to take the bait.

The ECB terminated its QE1 program at the end of 2018. Under the program, which started 1/22/15, the ECB’s “securities held for monetary policy purposes” increased by €2.4 trillion to €2.7 trillion (Fig. 6). Draghi’s QE2 program will once again expand the ECB’s balance sheet to new record highs.

(3) BOJ. In an 11/18 Reuters interview, Bank of Japan (BOJ) Governor Haruhiko Kuroda said the BOJ has room to deepen negative interest rates, but he signaled there were limits to how far it can cut rates or ramp up stimulus.

According to Reuters, “Kuroda also said there was still enough Japanese government bonds (JGB) left in the market for the BOJ to buy, playing down concerns its huge purchases have drained market liquidity. After years of heavy purchases to flood markets with cash, the BOJ now owns nearly half of the JGB market.”

The BOJ’s QE program started in April 2013 and has yet to be terminated. This can be seen in bank reserve balances at the BOJ. They rose to a record high of ¥352 trillion during November, up 740% since the start of the program (Fig. 7).

(4) All together now. The total assets of the Fed, ECB, and BOJ rose $264 billion y/y during November to $14.5 trillion (Fig. 8). On this basis, they had been falling from December 2018 through September 2019. This total is on track now to rise to record highs in 2020.

That should be good for the stock market, which has been tracking the total assets of the three major central banks since the start of the current bull market (Fig. 9). Don’t fight the three major central banks.

The main near-term risk is a meltup that could set the stage for a correction. My S&P 500 forecast for year-end 2020 is still 3500. I just hope we don't get there well ahead of schedule. See CNBC: "A 10% to 20% pullback could strike stocks early next year, long-time bull Ed Yardeni warns."

Actually, at the end of last year, Fed Chair Jerome Powell seemed more like a Grinch than a Santa. He roiled the financial markets by suggesting that the Fed would continue to raise the federal funds rate three or four times during 2019. He started to change his mind just around Christmas of last year and signaled that the Fed would halt rate hikes for a while. He completed his pivot by lowering the federal funds rate three times this year, on 7/31, 9/18, and 10/30 (Fig. 1).

As a result, the S&P 500 stock price index bottomed on Christmas Eve last year at 2351.10 (Fig. 2). It was up 37.8% to 3240.02 on Friday, 12/27 (Fig. 3). That’s a very long Santa Claus rally.

At the 7/31 meeting of the FOMC, the committee decided not only to lower the federal funds rate, for the first rate cut since 2008, but also to terminate quantitative tightening (QT) ahead of schedule: “The Committee will conclude the reduction of its aggregate securities holdings in the System Open Market Account in August, two months earlier than previously indicated.” From 10/1/17 through 7/31/19, the Fed’s balance sheet was pared from $4.4 trillion to $3.7 trillion (Fig. 4).

The Fed and the other major central banks are all playing Santa during this holiday season and are on track to continue doing so in the new year:

(1) Fed. In a 10/11 press release, the Fed announced that beginning on 10/15 it “will purchase Treasury bills at least into the second quarter of next year in order to maintain over time ample reserve balances at or above the level that prevailed in early September 2019.” More details were released in a separate New York Fed statement (and accompanying FAQs).

The initial pace of these “reserve management” (RM) purchases will be approximately $60 billion per month and will be in addition to ongoing purchases of Treasuries related to the reinvestment of principal payments from the Fed’s maturing holdings of agency debt and agency mortgage-backed securities. As the new holdings mature, the principal payments will be reinvested again into T-bills.

Many have commented that these actions look a lot like quantitative easing (QE). After all, the Fed is expanding its balance sheet sizably, possibly by up to $300 billion or more assuming $60 billion a month through March as a ballpark figure. The Fed’s balance sheet totaled $4.0 trillion during the 12/4 week, including $2.3 trillion in US Treasury securities, of which $420 billion are Treasuries maturing in one year or less (Fig. 5). This portfolio of Treasuries maturing in under a year is up $71 billion since the end of September.

(2) ECB. Mario Draghi’s term as president of the European Central Bank (ECB) ended on 10/31. Before leaving, Draghi put together a monetary stimulus package. It is designed to induce Eurozone governments to borrow at zero or negative interest rates to spend on stimulating their economies.

The package includes an open-ended commitment to buy as much as €240 billion per year of bonds issued by Eurozone governments. In other words, Draghi set the stage for the implementation of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) in the Eurozone. According to MMT, governments should borrow as much as possible as long as inflation doesn’t heat up. All the better if the central bank enables such borrowing by lowering interest rates and purchasing government bonds—again, as long as inflation doesn’t heat up. Now it is up to the various Eurozone governments to take the bait.

The ECB terminated its QE1 program at the end of 2018. Under the program, which started 1/22/15, the ECB’s “securities held for monetary policy purposes” increased by €2.4 trillion to €2.7 trillion (Fig. 6). Draghi’s QE2 program will once again expand the ECB’s balance sheet to new record highs.

(3) BOJ. In an 11/18 Reuters interview, Bank of Japan (BOJ) Governor Haruhiko Kuroda said the BOJ has room to deepen negative interest rates, but he signaled there were limits to how far it can cut rates or ramp up stimulus.

According to Reuters, “Kuroda also said there was still enough Japanese government bonds (JGB) left in the market for the BOJ to buy, playing down concerns its huge purchases have drained market liquidity. After years of heavy purchases to flood markets with cash, the BOJ now owns nearly half of the JGB market.”

The BOJ’s QE program started in April 2013 and has yet to be terminated. This can be seen in bank reserve balances at the BOJ. They rose to a record high of ¥352 trillion during November, up 740% since the start of the program (Fig. 7).

(4) All together now. The total assets of the Fed, ECB, and BOJ rose $264 billion y/y during November to $14.5 trillion (Fig. 8). On this basis, they had been falling from December 2018 through September 2019. This total is on track now to rise to record highs in 2020.

That should be good for the stock market, which has been tracking the total assets of the three major central banks since the start of the current bull market (Fig. 9). Don’t fight the three major central banks.

The main near-term risk is a meltup that could set the stage for a correction. My S&P 500 forecast for year-end 2020 is still 3500. I just hope we don't get there well ahead of schedule. See CNBC: "A 10% to 20% pullback could strike stocks early next year, long-time bull Ed Yardeni warns."