The following is an excerpt about Paul Volcker, who passed away on December 8, from my forthcoming book, Fed Watching for Fun and Profit.

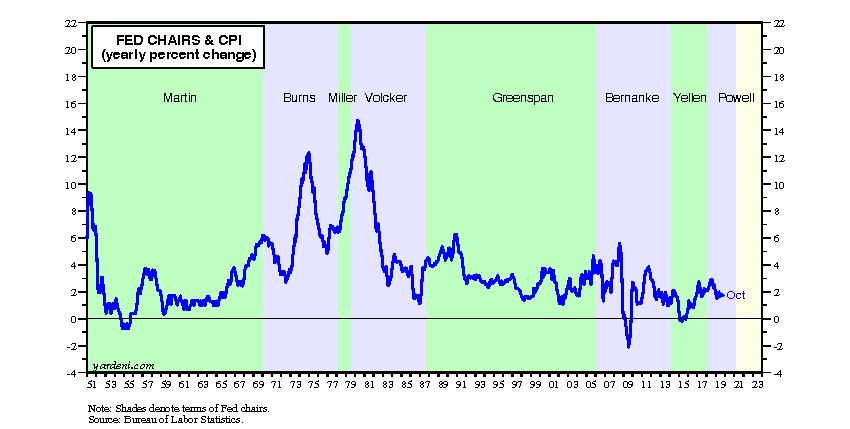

When Volcker took the helm of the Fed, the Great Inflation was well underway. During the summer of 1979, oil prices were soaring again because of the second oil crisis, which started at the beginning of the year when the Shah of Iran was overthrown. Seven months later, in March 1980, the CPI inflation rate peaked at its record high of 14.8%. When Volcker left the Fed during August 1987, he had gotten it back down to 4.3%.

How did he do that?

Volcker didn’t waste any time attacking inflation. Eight days after starting his new job, he had the FOMC raise the federal funds rate on August 14, 1979, by 50 basis points to 11.00%. Two days later, on August 16, he called a meeting of the seven members of the Federal Reserve Board to increase the discount rate by half a percentage point to 10.50%. This confirmed that the federal funds rate had been raised by the same amount. Back then, as I previously noted, FOMC decisions weren’t announced. The markets had to guess.

On September 18, 1979, Volcker pushed for another discount-rate hike of 50 basis points to 11.00%. However, this time, the vote wasn’t unanimous; the Board was split four to three. In his memoir, Volcker wrote that market participants concluded that “the Fed was losing its nerve and would fail to maintain a disciplined stance against inflation.” The dollar fell and the price of gold hit a new record high.

Volcker, recognizing that the Fed’s credibility along with his own were on the line, came up with a simple, though radical, solution that would take the economy’s intractable inflation problem right out of the hands of the indecisive FOMC and the Board: The Fed’s monetary policy committee would establish growth targets for the money supply and no longer target the federal funds rate.

This new procedure would leave it up to the market to determine the federal funds rate; the FOMC no longer would vote to determine it! This so-called “monetarist” approach to managing monetary policy had a longtime champion in Milton Friedman, who advocated that the Fed should target a fixed growth rate in the money supply and stick to it. Under the circumstances, Volcker was intent on slowing it down, knowing this would push interest rates up sharply.

On October 4, Volcker discussed his plan with the Board. In his memoir, he noted, “Even the ‘doves’ who had opposed our last discount-rate increase were broadly supportive, having been taken aback by the market’s violent reaction to the split vote.” A special meeting of the FOMC was scheduled for Saturday, October 6. Holding an unprecedented Saturday night press conference after the special meeting, Volcker unleashed his own version of the Saturday Night Massacre. He announced that the FOMC had adopted monetarist operating procedures effective immediately. He said, “Business data has been good and better than expected. Inflation data has been bad and perhaps worse than expected.” He also stated that the discount rate, which remained under the Fed’s control, was being increased a full percentage point to a record 12.00%. In addition, banks were required to set aside more of their deposits as reserves.

The Carter administration immediately endorsed Volcker’s October 6 package. Press secretary Jody Powell said that the Fed’s moves should “help reduce inflationary expectations, contribute to a stronger US dollar abroad, and curb unhealthy speculation in commodity markets.” He added, “The Administration believes that success in reducing inflationary pressures will lead in due course both to lower rates of price increases and to lower interest rates.”

The notion that the Fed would no longer target the federal funds rate but instead target growth rates for the major money supply measures came as a shock to the financial community. It meant that interest rates could swing widely and wildly. And they did. The economy fell into a deep recession at the start of 1980, as the prime rate soared to an all-time record high of 21.50% during December 1980. The federal funds rate rose to an all-time record high of 20.00% at the start of 1981. During 1980, the discount rate was raised to 13.00% on February 15, then lowered three times to 10.00%, then raised again two times back to 13.00%, on the way to the all-time record high of 14.00% during May 1981. The trade-weighted dollar index increased dramatically by 56% from 95 on August 6, 1979, when Volcker became Fed chair, to a record high of 148 on February 25, 1985.

The public reaction to Volcker’s policy move was mostly hostile. Farmers surrounded the Fed’s headquarters building in Washington with tractors. Homebuilders sent Volcker sawed-off two-by-fours with angry messages. Community groups staged protests around the Fed’s building. Volcker was assigned a bodyguard at the end of 1980. One year later, an armed man entered the building, apparently intent on taking the Board hostage.

At my first job on Wall Street as the chief economist at EF Hutton, I was an early believer in “disinflation.” I first used that word, which means falling inflation, in my June 1981 commentary, “Well on the Road to Disinflation.” The CPI inflation rate was 9.6% that month. I predicted that Volcker would succeed in breaking the inflationary uptrend of the 1960s and 1970s. I certainly wasn’t a monetarist, given my Keynesian training at Yale. I knew that my former boss [at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York] wasn’t a monetarist either. But I expected that Volcker would use this radical approach to push interest rates up as high as necessary to break the back of inflation.

Volcker must have known that would cause a severe recession. I did too. Back then, I called Volcker’s approach “macho monetarism.” I figured that a severe recession would bring inflation down, which in turn would force the Fed to reverse its monetary course by easing. That would trigger a big drop in bond yields. Arguably, the great bull market in stocks started August 12, 1982, when the Dow Jones Industrial Average dropped to 776.92. On December 6, 2019, it was 27,677.79.

Thank you, Paul Volcker.

When Volcker took the helm of the Fed, the Great Inflation was well underway. During the summer of 1979, oil prices were soaring again because of the second oil crisis, which started at the beginning of the year when the Shah of Iran was overthrown. Seven months later, in March 1980, the CPI inflation rate peaked at its record high of 14.8%. When Volcker left the Fed during August 1987, he had gotten it back down to 4.3%.

How did he do that?

Volcker didn’t waste any time attacking inflation. Eight days after starting his new job, he had the FOMC raise the federal funds rate on August 14, 1979, by 50 basis points to 11.00%. Two days later, on August 16, he called a meeting of the seven members of the Federal Reserve Board to increase the discount rate by half a percentage point to 10.50%. This confirmed that the federal funds rate had been raised by the same amount. Back then, as I previously noted, FOMC decisions weren’t announced. The markets had to guess.

On September 18, 1979, Volcker pushed for another discount-rate hike of 50 basis points to 11.00%. However, this time, the vote wasn’t unanimous; the Board was split four to three. In his memoir, Volcker wrote that market participants concluded that “the Fed was losing its nerve and would fail to maintain a disciplined stance against inflation.” The dollar fell and the price of gold hit a new record high.

Volcker, recognizing that the Fed’s credibility along with his own were on the line, came up with a simple, though radical, solution that would take the economy’s intractable inflation problem right out of the hands of the indecisive FOMC and the Board: The Fed’s monetary policy committee would establish growth targets for the money supply and no longer target the federal funds rate.

This new procedure would leave it up to the market to determine the federal funds rate; the FOMC no longer would vote to determine it! This so-called “monetarist” approach to managing monetary policy had a longtime champion in Milton Friedman, who advocated that the Fed should target a fixed growth rate in the money supply and stick to it. Under the circumstances, Volcker was intent on slowing it down, knowing this would push interest rates up sharply.

On October 4, Volcker discussed his plan with the Board. In his memoir, he noted, “Even the ‘doves’ who had opposed our last discount-rate increase were broadly supportive, having been taken aback by the market’s violent reaction to the split vote.” A special meeting of the FOMC was scheduled for Saturday, October 6. Holding an unprecedented Saturday night press conference after the special meeting, Volcker unleashed his own version of the Saturday Night Massacre. He announced that the FOMC had adopted monetarist operating procedures effective immediately. He said, “Business data has been good and better than expected. Inflation data has been bad and perhaps worse than expected.” He also stated that the discount rate, which remained under the Fed’s control, was being increased a full percentage point to a record 12.00%. In addition, banks were required to set aside more of their deposits as reserves.

The Carter administration immediately endorsed Volcker’s October 6 package. Press secretary Jody Powell said that the Fed’s moves should “help reduce inflationary expectations, contribute to a stronger US dollar abroad, and curb unhealthy speculation in commodity markets.” He added, “The Administration believes that success in reducing inflationary pressures will lead in due course both to lower rates of price increases and to lower interest rates.”

The notion that the Fed would no longer target the federal funds rate but instead target growth rates for the major money supply measures came as a shock to the financial community. It meant that interest rates could swing widely and wildly. And they did. The economy fell into a deep recession at the start of 1980, as the prime rate soared to an all-time record high of 21.50% during December 1980. The federal funds rate rose to an all-time record high of 20.00% at the start of 1981. During 1980, the discount rate was raised to 13.00% on February 15, then lowered three times to 10.00%, then raised again two times back to 13.00%, on the way to the all-time record high of 14.00% during May 1981. The trade-weighted dollar index increased dramatically by 56% from 95 on August 6, 1979, when Volcker became Fed chair, to a record high of 148 on February 25, 1985.

The public reaction to Volcker’s policy move was mostly hostile. Farmers surrounded the Fed’s headquarters building in Washington with tractors. Homebuilders sent Volcker sawed-off two-by-fours with angry messages. Community groups staged protests around the Fed’s building. Volcker was assigned a bodyguard at the end of 1980. One year later, an armed man entered the building, apparently intent on taking the Board hostage.

At my first job on Wall Street as the chief economist at EF Hutton, I was an early believer in “disinflation.” I first used that word, which means falling inflation, in my June 1981 commentary, “Well on the Road to Disinflation.” The CPI inflation rate was 9.6% that month. I predicted that Volcker would succeed in breaking the inflationary uptrend of the 1960s and 1970s. I certainly wasn’t a monetarist, given my Keynesian training at Yale. I knew that my former boss [at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York] wasn’t a monetarist either. But I expected that Volcker would use this radical approach to push interest rates up as high as necessary to break the back of inflation.

Volcker must have known that would cause a severe recession. I did too. Back then, I called Volcker’s approach “macho monetarism.” I figured that a severe recession would bring inflation down, which in turn would force the Fed to reverse its monetary course by easing. That would trigger a big drop in bond yields. Arguably, the great bull market in stocks started August 12, 1982, when the Dow Jones Industrial Average dropped to 776.92. On December 6, 2019, it was 27,677.79.

Thank you, Paul Volcker.

No comments:

Post a Comment